“Recycling” Makes Plastic Pollution Worse

Your blue bin is full of aluminum, cardboard — and misplaced hopes about plastic

If you’re like many people, you’ve always thought a numbered-triangle symbol on the bottom of a plastic container tells you it’s recyclable — giving you peace of mind that when you toss it into a blue bin, it will be turned into something else.

That’s not true. Those symbols are Resin Identification Codes (RICs). Numbered 1 through 7, they only identify the kind of plastic an item is made of. Far from giving a sweeping assurance that RIC-stamped items are recyclable, the symbol frequently indicates a particular item absolutely cannot be recycled.

Reluctant to burden citizens with figuring out which plastics are recyclable — a chore that could dampen participation and cause confusion as recyclability of various plastics changes over time — many municipal recycling programs simply encourage people to toss all their RIC-stamped plastics in the bin and let the recyclers sort it out.

Which ones do recyclers actually want? The most-recycled plastic in America is stamped with a “1,” identifying the item as polyethylene terephthalate (PET). You’ll find it on beverage bottles, cooking oil containers, and many other liquid-containing bottles. A “2” tells you it’s high-density polyethylene (HDPE). Another generally recycling-suitable plastic, it’s used for milk jugs and laundry detergent jugs, and spray-cleaner bottles.

It’s all downhill from there. Chances are your bin has plenty of #5 — polypropylene (PP) — which is frequently used for single-serve coffee-maker pods; yogurt, butter, prescription pill and soft tofu containers; and the lids on paperboard raisin cartons. Unfortunately, while there’s been a modest recent uptick in recyclers’ interest, polypropylene generally isn’t being recycled in the United States.

As for the rest of the RIC spectrum, feel free to make pointed inquiries with your city government, but chances are extremely slim that any #3, #4, #6 or #7 items you throw in your curbside blue bin will be made into anything else. That heap includes lots of packaging, such as non-cardboard egg cartons, fast-food clamshells, styrofoam cups and to-go containers, flexible 6-pack rings and bread bags.

Feeling a little demoralized? Brace yourself: This blue-bin buzzkill is just getting started.

Let’s circle back to recyclers’ favorite: #1 PET. Even for this most-favored plastic, much of what’s placed in blue bins isn’t recycled. It’s a question of configuration: Recyclers love clear PET bottles, but most of them don’t want PET when it’s in the form of clamshell containers, cups and tubs. In these formats, PET reacts differently to the heat of recycling. For example, if they’re combined with bottles, those PET tubs used to package your blueberries and strawberries create ash that contaminates the whole batch.

“This is a perfect example of why we don’t go by plastic numbers,” explains Millenium Recycling. “A #1 clamshell container is NOT the same as a #1 bottle and they cannot be recycled the same way.”

Size matters too. No matter the type of plastic, if it’s smaller than three inches, most recycling processors don’t want it cluttering up their works. Given that, the Washington Post recently advised simply throwing away any plastic that doesn’t fit in the palm of your hand. Thinness is another liability — which means your plastic forks, spoons and straws are also a no-go.

Then there’s color discrimination — any kind of black plastic is pretty much guaranteed not to be recycled, because infrared scanners in automated sorting machines aren’t able to “see” most black plastic. And while clear #1 PET bottles are at the top of the recyclability list, colored PET bottles are less favored.

The public’s falsely favorable perception of plastic recycling has been deliberately cultivated. Knowing consumers are increasingly concerned about the environmental impact of their purchase decisions, plastic manufacturers and product-packagers are quick to say a package is recyclable — failing to differentiate between plastics that are technically recyclable and those that are actually being recycled in practice.

Three plastics — #1 PET, #2 HDPE and #5 PP —have been granted the designation of “widely recyclable” by How2Recycle, a consortium founded by Exxon Mobil and other plastics producers. However, only about 2.7% of #5 PP is being recycled today. Regardless, you may see “widely recyclable” printed on a yogurt tub that has a slim chance of being recycled. Environmentalists have cried foul, urging the EPA to take control of such designations to prevent consumers from being misled.

However, governments get in on the deception too. Many cities, states and countries calculate their recycling rate based merely on what’s diverted from landfills — even if that plastic is incinerated or shipped off to another country where its fate is far from certain…more on that in a moment.

Mythology surrounding plastic recycling is also reinforced by a decades-long stream of public service ads. While they ostensibly encourage recycling, critics say their real purpose is divert the public from challenging plastic’s domination of packaging, by cultivating a falsely rosy view of what recycling is accomplishing.

The most famous such ad was the “crying Indian” commercial that debuted in 1971. More recently, you’ve surely seen the ad that shows a plastic bottle — personified with a vulnerable yet determined female voice — blowing down streets, roads and highways before finally being placed in a recycling bin by a passer-by, and then happily turned into a park bench overlooking the sea.

Neither the crying Indian nor the talking bottle are brought to you by environmentalists. They were underwritten by chemical and consumer product companies. While the ads are attributed to Keep America Beautiful, that entity is itself the creation of major packaging and beverage companies.

“The marketing of it, for decades, has been ‘You’re saving the Earth. That’s all you need to do, public. Keep consuming. You can do all this disposability and all you have to do is simply put it in that blue bin — your job as a citizen is done’,” the Burbank Recycling Center’s Amy Hammes told NPR. “So it led to more disposability, really, because we had that Get Out Of Jail Free card to ease our guilt.”

To a great extent, America’s entire recycling regime is the creation of the companies that profit from plastics. Staring down the barrel of proposed plastic bans in the late 1980s, big oil and chemical companies created The Council for Solid Waste Solutions, which funded municipal-recycling pilot programs.

“The industry attitude was, we’ll set this up and get it going, but if the public wants it, they are going to have to pay for it,” Ronald Liesemer, who was tasked with setting the wheels in motion told PBS. “Making recycling work was a way to keep their products in the marketplace.”

Today, it’s increasingly clear that plastic recycling isn’t working, and the most emphatic criticism is coming from environmentalists. “Plastic recycling is a dead-end street,” Greenpeace bluntly declared in a 2022 report that concisely summed up plastic recycling’s empty environmental promise:

“Mechanical and chemical recycling of plastic waste has largely failed and will always fail because plastic waste is: extremely difficult to collect, virtually impossible to sort for recycling, environmentally harmful to reprocess, often made of and contaminated by toxic materials, and not economical to recycle.”

It’s important to note that, unlike infinitely-recyclable aluminum, plastic can only be recycled two or three times before it degrades beyond usefulness. And unlike the aluminum, recycled plastic costs a lot more than new plastic.

Despite more than a generation of effort, only 8.7% of plastic waste is being recycled in the United States, according to the EPA’s most recent data, compared to 68.2% of paper and cardboard and 50.4% of aluminum — materials you can put in your blue bin with relative contentment.

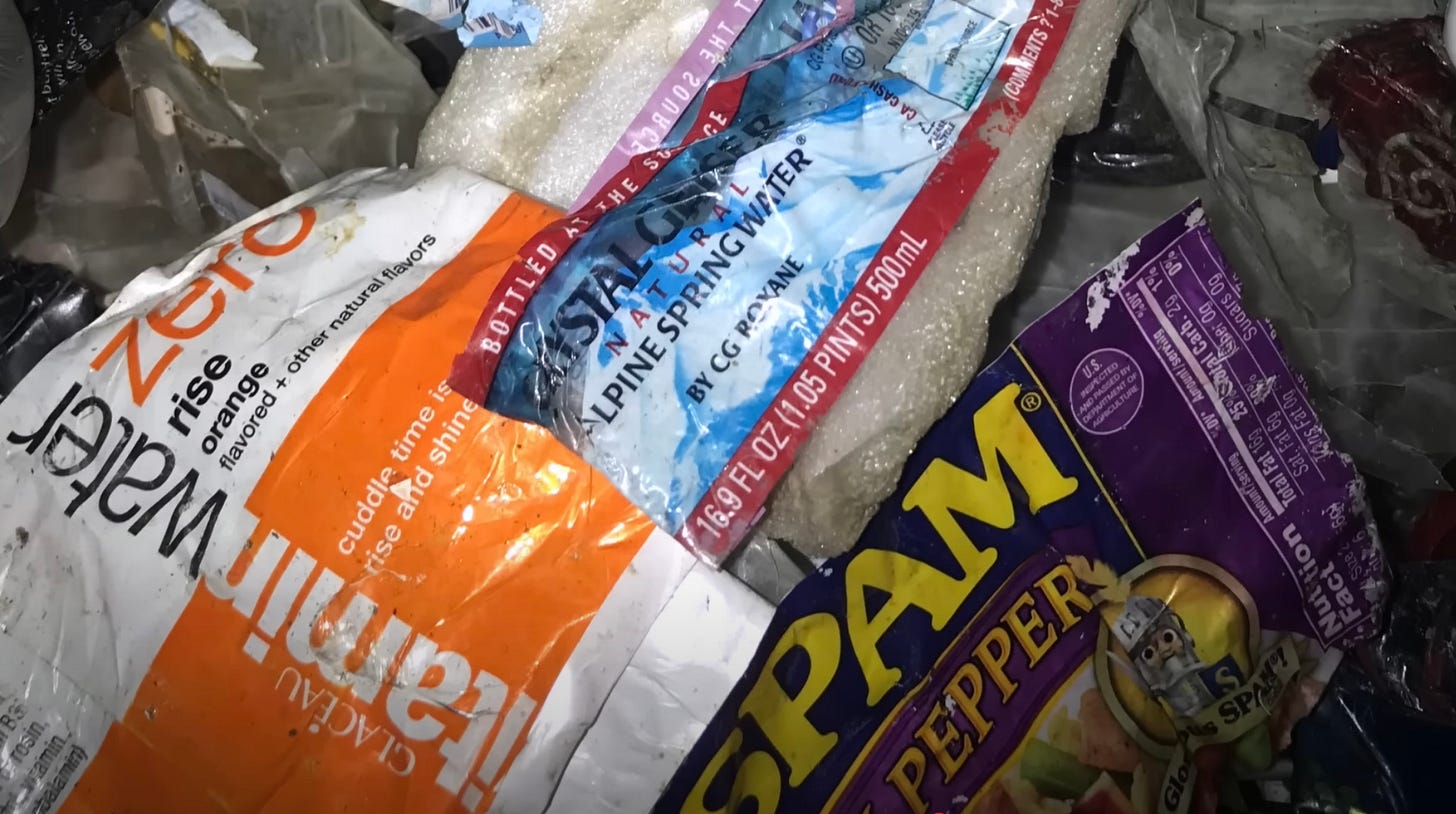

What happens to all the plastic that’s rejected by recyclers? It may be incinerated or sent to a landfill. That’s the good news. Believe it or not, some of plastic that Americans diligently “recycle” is dumped into rivers, fields or oceans halfway around the Earth.

America has long shipped much of its unwanted plastic overseas. For years, China was the largest importer by far, using cheap labor to pick by hand through millions of tons of plastic. Irresponsible handling of all that material — from toxic open-air burn-piles to illegal dumping of undesirable plastic— meant China was also importing pollution on an enormous scale.

In 2018, China effectively slammed the door shut on the import of plastic trash. However, other developing countries stepped up; among them, Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia. Predictably, the same terrible practices that caused China to change course are being observed in these countries too, with processors extracting the “good stuff” from piles of unsorted plastic and putting the rest wherever they feel like it.

Just as the road to Hell is paved with good intentions, it turns out the plastic “recycling” stream may ultimately deposit your #5 yogurt tub or #1 blueberry carton into an Asian river, and then the Pacific Ocean.

Delusions about plastic recycling contribute to collateral harms at home too. “If you rinse a plastic bottle in hot water, the net result is more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than if you threw it in the garbage,” former New York Times science writer John Tierney told John Stossel.

That’s tough enough to hear in the context of a bottle that actually gets recycled. Now imagine the incalculable volume of hot water that’s been pointlessly poured on plastics that never had a prayer of being recycled — because local governments didn’t want to burden citizens with the truth about recycling’s viability.

Even at its best moments, plastic recycling is itself a source of waste and pollution. In processing a batch of those relatively-prized #1 PET bottles, about 30% of the material is typically wasted and must be disposed of. Meanwhile, the processing of plastic trash consumes energy, with much of the energy consumed by processing plastic that won’t be recycled. All that processing also generates microplastics, and the release of toxins associated with the thousands of chemicals that are added to plastics in the original manufacturing process.

“Americans support recycling. We do too,” wrote former EPA administrator Judith Enck and Last Beach Cleanup founder Jan Dell at The Atlantic. “But although some materials can be effectively recycled and safely made from recycled content, plastics cannot. Plastic recycling does not work and will never work.”

Since the 1970s, environmentalists have used the slogan “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle.” To some, the biggest collateral harm of plastic recycling is that it shifts attention away from the “Reduce” component — reducing the production of plastic in the first place, by replacing it with an alternative.

While it’s universally resented, plastic dominates packaging because of its many beneficial attributes — which include being lightweight, inexpensive and durable. Amid broad yearning for plastic to be replaced — perhaps via government dictates — we should all keep in mind economist Thomas Sowell’s invaluable caution about any policy question: “There are no solutions, only trade-offs.”

If you replace plastic with something heavier, transporting it will consume more energy. More weight on truck tires means they wear faster — and tires are themselves a major generator of microplastics.

If you replace plastic with something more expensive, you make food and other products less affordable — especially for poor people.

If you replace plastic with something less durable and sealable, you’ll increase contamination, spoilage, and maybe even sickness.

One potential replacement is bioplastic made from corn or sugar beets. Such a “natural” solution has instinctive appeal, but critics say bioplastics can have an even worse environmental impact, thanks to emissions associated with agriculture. Similarly, researchers last year concluded that alternatives like glass, paper and metals have worse greenhouse gas emission profiles than plastic.

That’s not to say we should throw in the towel on seeking viable plastic alternatives that have a better end-to-end environmental profile. In the meantime, however, a case can be made that the best way to handle our plastic trash is to send it straight to landfills, rather than continuing to embrace a fiction plastered over the hard truth of plastic recycling. After all, much of your “recycled” plastic is going to landfills already.

Instinct may tell you that putting an empty blueberry carton in a landfill is nearly as bad as throwing it in a river. If so, it may be because your vision of a landfill doesn’t match the reality of today’s modern, regulated facilities. As civil engineer and hydrologist BJ Campbell explains:

[Modern landfills] are sealed on the bottom with geotechnical fabric to prevent leachate from entering the groundwater. They burn off, or sometimes even harvest, the methane produced from decomposition. Landfill cells are capped off with clay or bentonite to protect the environment. And then often they’re turned into parks or golf courses at the end.

What about decomposition and seepage into the soil? Modern landfills have an ongoing mechanism for collecting that liquid waste — or “leachate” — the collects at the bottom.

Researchers from the University of Illinois who scoured the leachate flowing from four landfills were pleasantly surprised by the low volume of microplastics they found. In a 2024 study published in Science of the Total Environment, they reported that landfills “retain most of the plastic waste that is dumped there, and wastewater treatment plants remove 99% of the microplastics…from the wastewater and leachate” that comes from the landfills.

Lest this sound like a landfill PR piece, note that researchers found higher levels of a different type of contaminant — PFAS, aka “forever chemicals” — than they expected. We should also acknowledge that, despite the promising findings regarding plastic retention in the examined landfills, no man-made system is immune to failures.

It’s often said that we’re going to run out of space for all our trash. In turns out that widely-held assumption is, well, rubbish. “If you think of the United States as a football field, all the garbage that we will generate in the next one thousand years would fit inside a tiny fraction of the one-inch line,” notes science writer Tierney.

Eliminating largely fictional plastic “recycling” and sending plastic straight to landfills isn’t an appealing choice, but it bears repeating: There are no solutions, only trade-offs.

Where environmental issues are concerned, the sheer volume of trade-offs is dizzying. Amid that daunting cloud of variables, one thing is certain: From the question of what to do with today’s plastic to the pursuit of viable plastic alternatives, rational evaluation of trade-offs is impeded by mythology that masks the stark realities of plastic-recycling.

Why not incinerate it, generate electricity, clean up the exhaust gas and landfill the ash?

Plastic recycling isn’t the cure—it’s the con. The industry sold us a fairy tale, a neat little loop of redemption where our waste is reborn, but in truth, it's just a slow-motion disaster. Every cycle shreds plastic into smaller, more insidious ghosts—microplastics infiltrating our blood, our bones, our unborn children.

"Recycling is not a solution to the plastic pollution crisis; it is a distraction that allows the industry to continue its harmful practices unchecked."

Damn right. The machine runs on illusion, feeding us moral pacifiers while it cranks out more waste, more poison, more profit. If we want out, we don’t recycle—we reject. >lesscleardotcom