Flurry of Calls Among Saudi Diplomatic Staff and Spy Coincided With 9/11 Hijackers’ US Arrival

Future al Qaeda cleric Anwar al-Awlaki also connected

This is my second article based on an examination of several hundred recently-declassified documents from the FBI’s investigation of Saudi government links to 9/11. The first was FBI Mistakenly Names Saudi Consulate Employee Eyed in 9/11 Investigation.

FBI agents investigating Saudi ties to 9/11 discovered a set of phone calls among Saudi embassy and consulate officials, an extremist American cleric and a Saudi agent in San Diego—calls that took place in the weeks leading up to the first two hijackers’ arrival in Los Angeles and while they were settling in.

The timing raises suspicions of a premeditated scheme to shepherd the hijackers into American life—and some of the call participants personally did just that.

The phone links are described across thousands of pages of FBI documents released between September 2021 and April 2022. Many of the documents are from Operation Encore, an FBI investigation of Saudi government ties to the 9/11 plotters.

The first two hijackers to reach the United States were Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi, who acted as “muscle” hijackers on American Airlines Flight 77, which struck the Pentagon.

According to a 2008 Operation Encore document, “multiple San Diego sources and other individuals associated with al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi during their time in southern California believed that the two hijackers must have been given ‘tazkia’ prior to arriving in the United States.”

The document defines “tazkia” as one person’s vouching for another. Someone already in America “would then, because of this individual’s relationship with the tazkia-providing individual, have provided any and all assistance that al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi would need during their time in the United States.”

Hazmi and Mihdhar spoke very little English upon their arrival, to the extent of not even being able to read street signs. The two hijackers’ “only qualifications appeared to be support for [Osama bin Laden] and their ability to obtain visas,” says an FBI report.

Given their unfamiliarity with the United States and its language, it seems certain these first two hijackers on U.S. soil would have indeed needed help from people already in the country.

That help came, and phone records suggest it was pre-arranged, facilitated and supervised by Saudi government officials, employees and an intelligence asset.

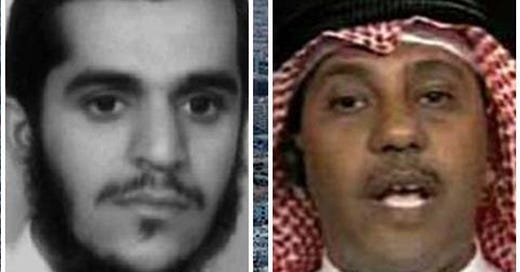

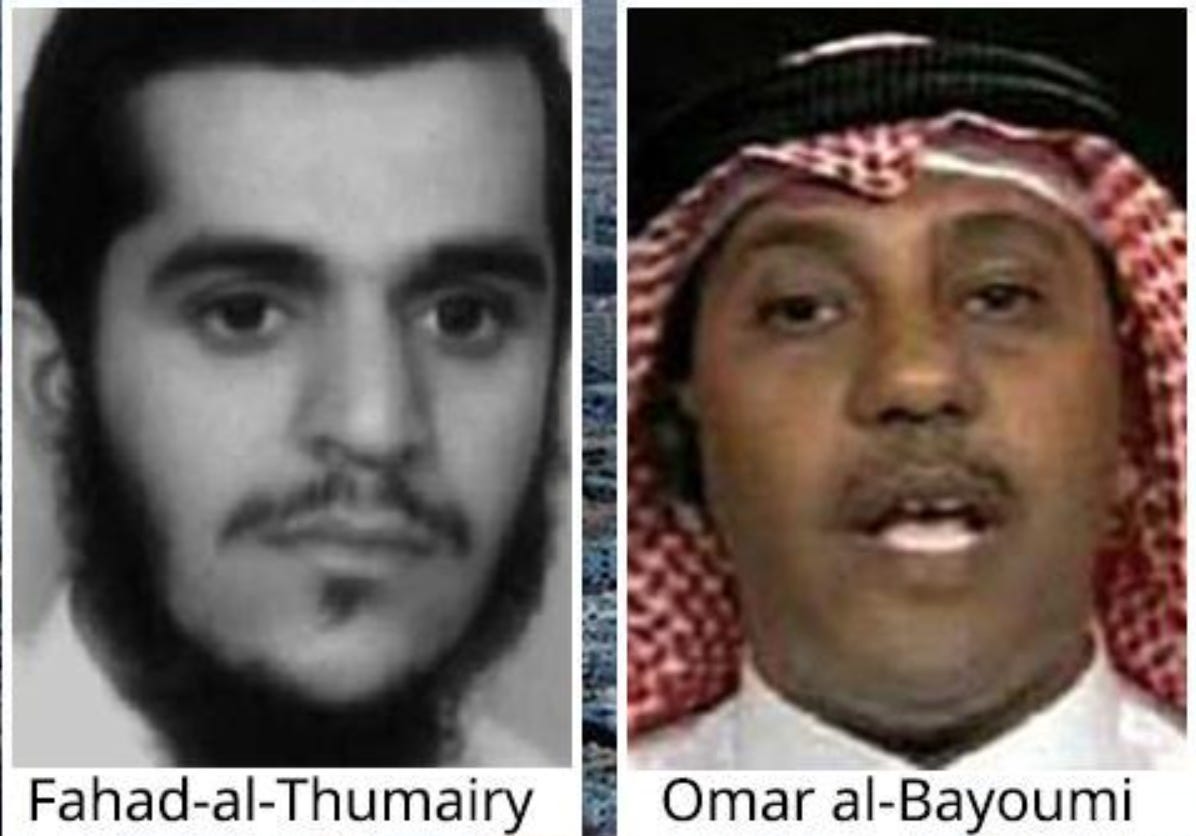

Mihdhar and Hazmi arrived in Los Angeles in January 2000. Soon after, one of the men involved in the flurry of phone calls, Omar al-Bayoumi, met the two, invited them to move to San Diego, and facilitated their renting of an apartment and other facets of becoming situated in the United States.

A 2017 FBI document declared that “recent source information confirmed that al-Bayoumi was, at the time of the 9/11 attacks, employed as a paid cooptee of Saudi Arabian intelligence services.” A 2006 document says he later provided “substantial financial support” to a Kurdish Salafist group formed by former al Qaeda and Taliban members.

In addition to Bayoumi, another key figure in the Operation Encore files was Fahad al-Thumairy, an official at the Saudi consulate in Los Angeles described as a “Salafi fanatic.”

Thumairy was at the center of a burst of phone activity leading up to and following the hijackers’ arrival. According to an Operation Encore document:

“During a three-day period at the end of December 1999, approximately two and a half weeks prior to the arrival of Al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi, Al-Thumairy made a number of phone calls that are significant in that the pattern of contact, including individuals and frequency, does not appear to have been duplicated prior to nor after this date.” . . .

“[Southern District of New York] feels that these telephonic contacts prior to the arrival of al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi are an important turning point in these investigations. It shows a prior relationship between these individuals who, in the upcoming months, have extensive telephonic and face-to-face contact with al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi.”

Twenty-one calls involving Thumairy during this time included contacts with:

Bayoumi, the Saudi intelligence asset who helped the hijackers

Anwar al-Awlaki, a U.S. citizen who later rose to infamy as an al-Qaeda cleric and organizer killed in a 2011 drone strike in Yemen. In 2000, Awlaki was an imam at a southern California mosque. He’d later move to northern Virginia at a time when some of the hijackers had also situated themselves there.

A “Somali/Yemeni student” in San Diego whose name is redacted. While redactions always leave some uncertainty, the document appears to indicate this individual’s phone had contact with a phone number in Yemen that served as an international al Qaeda switchboard.

The Saudi embassy in Washington

The Islamic Affairs section at the Saudi embassy

While the first document doesn’t name the individuals Thumairy talked to at the Saudi embassy in Washington, another file indicates his contacts there included:

Adel al-Sadhan, an Islamic Affairs section employee working for Mussaed al-Jarrah, another Saudi embassy official of FBI interest. “Al-Sadhan is believed to help al-Jarrah support extremist Saudi Sunnis in the United States,” said the FBI.

Mutaib al-Sudairy, an embassy administrative officer who later moved to Kansas and lived with an al Qaeda procurement officer said to have provided the phones used in the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in Africa.

According to an FBI report:

“[REDACTED] along with telephone and financial analysis, indicates Al-Sadhan and al-Sudairy may have assisted in laying the groundwork for the arrival of al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar in southern California and served as an advance team to vet those who would later assist both hijackers.”

Their alleged advance team activity extended well before the hijackers arrived.

A 2010 FBI report says Sadhan first visited Los Angeles and Thumairy in December 1998: “Investigators believe his visit was to begin preparations for al-Thumairy’s subsequent assistance to al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar.” Another document says Sudairy and Sadhan visited San Diego for six weeks in the summer of 1999 and were hosted by Bayoumi.

On December 12, 1999—about a month before the hijackers arrived—a Saudi individual named al-Jraithen arrived in Los Angeles and was registered at a hotel where Bayoumi was also registered.

Phone records point to Thumairy, Bayoumi and Awlaki being involved with Jraithen’s visit, along with another Los Angeles consulate employee, Mohammed al-Muhanna, who’s elsewhere described as an “Islamic extremist associated with a radical form of Salafi ideology” and who is “heavily connected/linked to Saudi Sunni extremists operating inside the U.S.”

An FBI agent, after noting some redacted indications that Jraithen’s visit held great importance, wrote, “It is possible that al-Jraithen provided the tazkia for al-Mihdar and al-Hazmi, ensuring that when the hijackers arrived the following month, they were taken care of by a network of individuals in Southern California.”

The hijackers arrived in Los Angeles on January 13, 2000. According to a 2008 FBI document, a “confidential human source” told investigators about a call from overseas made to the King Fahad Mosque in Los Angeles where al-Thumairy was an imam.

The source said someone asked for al-Thumairy and stated “the guys” were coming and needed to be picked up at the airport; the source understood “the guys” was a reference to Mihdhar and Hazmi.

FBI files say a man named “Johar”—likely Mohammed Johar—was “tasked” by Thumairy to pick up the hijackers at LAX and “take care of them during their time in Los Angeles.” Two days after their arrival, Thumairy made several calls to Saudi Arabia.

About two weeks after the hijackers landed, Bayoumi first met them at a Mediterranean restaurant in Los Angeles. He invited them to move to San Diego, where he lived.

Bayoumi later told U.S. investigators it was a chance encounter, but it came within a couple hours after he had a meeting at the Saudi consulate with an employee described as having “extremist views.” As Stark Realities was first to report last month, in its declassification, the FBI inadvertently revealed that man’s name is “Mana.”

On that same pivotal day, Bayoumi had a six-minute call with the Saudi embassy. He also received a $10,000 wire transfer from a man the FBI believed to be a brother-in-law who “worked for the PC.” It’s not clear what that abbreviation means. One former agent I spoke to wonders if the author mistakenly dropped an “A” in a reference to the Saudi Presidency of Civil Aviation or PCA, an entity that paid Bayoumi’s salary for a no-show job at a Saudi government contractor in California.

Suspicious calls continued after the hijackers moved to San Diego:

“Al-Bayoumi called al-Sudairy five (5) times while the hijackers were in San Diego with al-Bayoumi. The dates of the calls are significant. The first set of calls are 24 January, 26 January, and 30 January 2000—on these particular days al-Bayoumi met the hijackers in Culver City, CA and talked to them about coming to San Diego. The next call occurred on 2 February 2000. On 4 February 2000, al-Bayoumi co-signed a loan agreement for the apartment he obtained for the hijackers and brought them to a Bank of America to assist them in opening a bank account.

An hour after Bayoumi helped the hijackers open the account, Awlaki called a Bank of America number. Two hours after that, Bayoumi called Awlaki.

Bayoumi’s final call to al-Sudairy at the Saudi embassy came on February 7, 2000, after the hijackers were fully settled in the same apartment complex where Bayoumi lived.

Five hundred eighty-two days later, Hazmi and Mihdhar passed through security at Dulles Airport and boarded American Airlines Flight 77.

Stark Realities undermines official narratives, demolishes conventional wisdom and exposes fundamental myths across the political spectrum. Read more and subscribe at starkrealities.substack.com

There’s much more for interested readers to learn about what went on in southern California ahead of 9/11, including more participants and additional links to the Saudi embassy—to include Saudi ambassador Prince Bandar himself. Check out my previous article: FBI Mistakenly Names Saudi Consulate Employee Eyed in 9/11 Investigation.

Excellent work, Brian. Some of the documents are being released/declassified now because for far too many Americans, this is down the memory hole and gone. As well as the bogus excuses under which USA launched the Second Gulf War. In general terms, but not with the key details, I think the greater Saudi involvement was known or suspected at the time. Robert Baer's See No Evil (2003) remains a classic. Accounts like yours will be essential if and when serious historians want to account for what happened and why. Given our current fixations on Putin and our efforts to provoke China into invading Taiwan, however, I am regretfully not sure work like yours will get the attention it deserves. All best!

A foreigner making lots of calls to the short list of people they know in a new country proves they don’t know many people in the new country. Nothing in this article tells us what they discussed in the calls.

Besides, if the FBI was actually on to these guys and monitoring their calls, why the $&#* didn’t the FBI stop them? If the calls in this post are incriminating, it means the FBI were co-conspirators.